The Outer Banks, tenuous bands of sand that lie less than 40 miles inside the Gulf Stream and, in places, more than 20 miles from the North Carolina mainland, are a geological wonder. These barrier islands are accessible only by bridges, boats or planes. Their remoteness, fragility and continual exposure to sea and storms give these Outer Banks islands and inlets a constantly changing aspect. Born in swirling seas and abandoned by retreating mother earth, the Outer Banks’ dreamy genesis reminds one of Hilton’s paradisial Shangri-La.

The Outer Banks in the Beginning…

When the sinking sea reached its lowest level and winds began carrying sediment from the west, a high ridge of sand dunes formed on the easternmost edge of the mainland. Glaciers began to melt. The sea level began to rise. And the land’s vast forests and marshes began a slow retreat away from the rising waters. In their wake, they left huge river deltas rich in materials. Those materials ultimately formed the Outer Banks.

Today, the islands’ eastern edges still move backward in response to rising waters. On the west side, they build up. Narrowing the wide series of brackish water called sounds that separate the barrier islands from the mainland. Sea levels continued to rise over the next few thousand years, but the newly formed barrier islands that paralleled Carolina’s coast weren’t covered by the higher tides. Instead, an unusual combination of winds, waves and weather enabled the Outer Banks to maintain its elevation above the ocean and to migrate as a unit.

Ocean levels rise about a foot every 100 years. The shoreline moves westerly at a rate of 50 to 200 feet per century along most of North Carolina’s coast. On parts of Hatteras Island, the Atlantic eats 14 feet of beach each year.

Geologists refer to the Outer Banks and similar land forms as “barrier islands” because they block the high-energy ocean waves and storm surges, protecting the coastal mainland. Barrier islands are common to many parts of the world, and many have similar features, yet no two are alike. Winds, weather and waves give each its own personality. Inlets from the sounds to sea are ever shifting, opening new channels to the ocean one century, closing off primary passageways the next. And folks who venture from one area of the Outer Banks to another soon will realize even along this small stretch of sand that there is a vast variety of topography, flora and temperatures.

Geologists refer to the Outer Banks and similar land forms as “barrier islands” because they block the high-energy ocean waves and storm surges, protecting the coastal mainland. Barrier islands are common to many parts of the world, and many have similar features, yet no two are alike. Winds, weather and waves give each its own personality. Inlets from the sounds to sea are ever shifting, opening new channels to the ocean one century, closing off primary passageways the next. And folks who venture from one area of the Outer Banks to another soon will realize even along this small stretch of sand that there is a vast variety of topography, flora and temperatures.

Early Outer Banks Explorers

Jutting far into the ocean near the warm waters of the Gulf Stream, the Outer Banks was the first North American land reached by English explorers. A group of colonists dispatched by Sir Walter Raleigh set up the first English settlement on North American soil in 1587. But Native Americans inhabited these barrier islands long before white men and women arrived.

Jutting far into the ocean near the warm waters of the Gulf Stream, the Outer Banks was the first North American land reached by English explorers. A group of colonists dispatched by Sir Walter Raleigh set up the first English settlement on North American soil in 1587. But Native Americans inhabited these barrier islands long before white men and women arrived.

Historians say humans have been living in North Carolina for more than 10,000 years. Three thousand years ago, people traveled throughout the Outer Banks hunting, fishing and feeding off the forest. The Carolina Algonkian culture, a confederation of 75,000 people divided into distinct tribes, spread across 6,000 square miles of northeastem North Carolina.

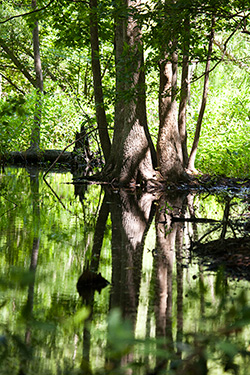

Archaeologists believe that as many as 5,000 Native Americans could have inhabited the southern end of Hatteras Island from 1000 to 1700 AD. These Native Americans formed the only island kingdom of the Algonkians. Isolation afforded these people protection and the sole use of the island's seemingly limitless resources. The Croatan lived comfortably for more than 800 years in the protection of the Buxton Woods Maritime Forest at Cape Hatteras. Contact with Europeans proved fateful, however. Disease, famine and cultural demise had eliminated all traces of the Carolina Algonkians by the 1770s.

Early ventures to America's Atlantic seaboard proved difficult for European explorers because of the high winds, seething surf and shifting sandbars. In 1524 Giovanni de Verrazzano, an Italian in the service of France, plied the waters off the Outer Banks in an unsuccessful search for the Northwest Passage. Verrazzano thought the barrier islands looked like an isthmus and the sounds behind them, an endless sea. According to historian David Stick, the explorer reported to the French king that these silvery salt waters must certainly be the "Oriental sea ... which is the one without doubt which goes about the extremity of India, China and Cathay." This explorer's misconception, that the Atlantic and Pacific oceans were separated by only the skinny strip of sand we now call the Outer Banks, was held by some Europeans for more than 150 years.

About 60 years after Verrazzano's visit, two English boats arrived along the Outer Banks, searching for a navigable inlet and a place to anchor away from the ocean. The captains, Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe, had been dispatched by Sir Walter Raleigh to explore the New World's coast. They were hoping to find a suitable site for an English settlement.

The explorers finally found an entrance through the islands above Cape Hatteras, probably at the present-day Ginguite Creek north of Kitty Hawk. They sailed south through the sounds until arriving at Roanoke Island. There, they disembarked, met the natives and marveled at the abundant wildlife and cedar trees. Their expedition had been successful, and they reported to Raleigh on the riches they had found and kindness with which the Native Americans had received them.

During the next three years, at least 40 English ships visited the Outer Banks, more than 100 English soldiers spent almost a year on Roanoke Island, and Great Britain began to gain a foothold on the continent, much to the dismay of Spanish sailors and fortune seekers.

Lost Colonists

May of 1587 three English ships commanded by naturalist John White set sail for the Outer Banks with Sir Walter Raleigh's (thus Queen Elizabeth's) blessing and backing. Earlier explorers had dubbed the land "Virginia," in honor of the virgin queen Elizabeth. The expedition, which included women and children for the first time, arrived at Roanoke Island on July 22. Colonists worked quickly to repair the cottages and military quarters left by the earlier British inhabitants. They fixed up a fort the soldiers had abandoned on the north end of the island and made plans for a permanent settlement. Less than a month later, the first English child was born on American soil. Virginia Dare, granddaughter of Gov. John White, was born on August 18, a date still celebrated with festivities at Fort Raleigh National Historic Site.

May of 1587 three English ships commanded by naturalist John White set sail for the Outer Banks with Sir Walter Raleigh's (thus Queen Elizabeth's) blessing and backing. Earlier explorers had dubbed the land "Virginia," in honor of the virgin queen Elizabeth. The expedition, which included women and children for the first time, arrived at Roanoke Island on July 22. Colonists worked quickly to repair the cottages and military quarters left by the earlier British inhabitants. They fixed up a fort the soldiers had abandoned on the north end of the island and made plans for a permanent settlement. Less than a month later, the first English child was born on American soil. Virginia Dare, granddaughter of Gov. John White, was born on August 18, a date still celebrated with festivities at Fort Raleigh National Historic Site.

One week after his granddaughter was baptized, John White left her and 110 other colonists on the Outer Banks while he returned to England for food, supplies and additional recruits for the Roanoke Island colony. A war with Spain, meanwhile, had broken out. So when White was again ready to set sail for the Outer Banks the following spring, his queen refused to let any large ships leave England, except to engage in battles. White did not get back to the American settlement until 1590. By then, it had disappeared.

The houses were gone, destroyed and deserted. White's own sea chests had been dug from their shallow hiding places in the sand, broken open, their contents raided. His daughter, granddaughter and all the other English colonists had vanished -- leaving no trace except for two cryptic carvings in the bark of Roanoke Island trees. "CRO" was scratched into the trunk of one tree near the bank of the Roanoke Sound. "CROATOAN" was etched into another, near the deteriorating fort. White thought these mysterious messages meant the settlers had fled south to live with the friendly Croatan Indians on Hatteras Island.

The abandoned settlement site showed no signs of a struggle, no blood, bodies or even bones. Some say the colonists were killed by natives or carried away in a skirmish. Others think they were lost at sea, trying to sail home to England. Still others believe they skirted west across the sounds and began to explore the Carolina mainland. Or perhaps they headed to other areas of the Outer Banks, their footsteps scattered in the blowing sands....

Historians have debated the Lost Colony's fate for more than 400 years. Archaeologists have continued to dig on Roanoke Island's eastern edges and beyond. Scholars from across the country have gathered to discuss the strange disappearance and established a special research office on the subject at East Carolina University in Greenville, led by archaeologist David S. Phelps of East Carolina University's Coastal Archeology Office. In 1998 a 10-caret gold signet ring engraved with a lion or horse head was unearthed at a site called Cape Creek on Hatteras Island. The ring is believed to date from the 16th century. Also found was a small piece of slate and an iron rapier mingled in with other artifacts of both English and Native American origin, supporting a theory that at least part of the English colony followed their Native American neighbors south.

In summer 2015, evidence discovered from a hidden section of a watercolor map drawn by John White placed the colonists inland, near present-day Edenton, approximately 50 miles from Roanoke Island. A group there, led by archaeologist Nicholas Luccketti of the First Colony Foundation, has unearthed pottery shards of the sort the colonists brought from England. Additionally, pieces of early gun flintlocks, a metal hook and a small copper tube have been discovered, none of which would have been in the possession of the native people who resided in a nearby village named Mettaquem. The researchers feel this is strong evidence that the colony, or at least part of them, went with these local allies as a means of survival.

Each summer, for more than a half-century, actors have recreated the unsolved mystery in America's longest running outdoor drama, The Lost Colony, held at the settlement site in Waterside Theatre.

Shipping and Settlement into the 1700s

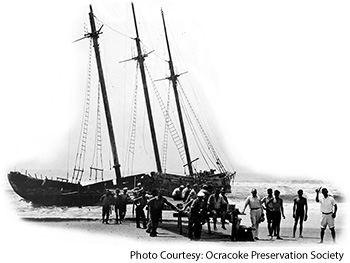

A century passed before English explorers again attempted to establish settlements along the Outer Banks. Throughout this time, however, European ships continued to explore the Atlantic seaboard, searching for gold and conquerable land. Scores of these sailing vessels wrecked in storms and on dangerous shoals east of the barrier islands. Spanish mustangs, some say, swam ashore from the sinking ships on which they were being transported overseas. Descendants of these wild stallions roam the beaches north of Corolla. Others are corralled in a National Park Service pen on Ocracoke Island.

A century passed before English explorers again attempted to establish settlements along the Outer Banks. Throughout this time, however, European ships continued to explore the Atlantic seaboard, searching for gold and conquerable land. Scores of these sailing vessels wrecked in storms and on dangerous shoals east of the barrier islands. Spanish mustangs, some say, swam ashore from the sinking ships on which they were being transported overseas. Descendants of these wild stallions roam the beaches north of Corolla. Others are corralled in a National Park Service pen on Ocracoke Island.

Although the Outer Banks beaches had few permanent English-decent people until the early 1700s, small colonies sprouted up across the Virginia coast and what is now the Carolina coast during the late 1600s. The barrier islands blocked deep-draft ships from sailing into safe harbors, where they needed to anchor and unload supplies for mainland settlers. Smaller vessels, fit for navigating the shallow sounds, transported goods from the Outer Banks to the mainland. People passed through these strips of sand long before they settled here.

Ocracoke Inlet, between Ocracoke and Portsmouth islands, was the busiest North Carolina waterway during much of the Colonial period. The inlet was a vital yet delicate link in the trade network, and it was deeper than most other area egresses. Navigational improvements to the inlet began as early as 1715 when the British government made it an official port of entry. Pilot houses were set up at Ocracoke to dock the small transport boats and temporarily house goods headed inland. Commercial traffic increased along this Outer Banks waterway for many years.

Ocracoke Inlet, between Ocracoke and Portsmouth islands, was the busiest North Carolina waterway during much of the Colonial period. The inlet was a vital yet delicate link in the trade network, and it was deeper than most other area egresses. Navigational improvements to the inlet began as early as 1715 when the British government made it an official port of entry. Pilot houses were set up at Ocracoke to dock the small transport boats and temporarily house goods headed inland. Commercial traffic increased along this Outer Banks waterway for many years.

Countless inlets from the sea to sound have formed and closed since the barrier islands first formed. More than two dozen inlets appear in the historical record and on maps dating from 1585. Yet only six inlets currently are open between Morehead City and the Virginia border. Studies of geographic formations and soil deposits indicate that, at some point in time, inlets have covered nearly 50 percent of the Outer Banks. Attempts to harness the inlets have proven costly and, for the most part, have been doomed to fail. Even today, recreational and commercial watermen continue to fight the shoaling in Oregon Inlet, which separates Nags Head and Bodie Island from Hatteras Island.

The first land the British government granted in North Carolina was what is now Colington Island, a small spit of earth surrounded by the Currituck, Albemarle and Roanoke sounds. Sir John Collenton, for whom the island is named, set up a plantation on the island’s sloping sand hills in 1664. His agents planted corn, built barns and houses and carried cattle across by boat to graze on the scrubby marsh grasses. According to historians, this was the beginning of the Outer Banks’ first permanent English settlement.

Over the next several decades, stockmen and farmers set up small grazing stocks and gardens on the sheltered sound side of the Outer Banks. Runaways, outlaws and entrepreneurs also arrived in small numbers, stealing away in the isolated forests, living off the fresh fish and abundant waterfowl and running high-priced hunting parties through the intricate bogs and creeks. Inhabitants also engaged in salvaging: When a shipwrecked vessel floated onto the shore, local residents made quick work of wielding the wood off the boat, loosening sails from the masts and scavenging anything of value that was left on board. If victims were still struggling ashore, the locals helped them, even setting up makeshift hospitals in their humble homes.

The inaccessibility of the barrier islands and wealth of goods that passed through the ports made the Outer Banks a prime target for plundering pirates. The most infamous of all high seas henchmen was Edward Teach, better known as Blackbeard, a rum-drinking Englishman whose raucous crew set up shop on the south end of Ocracoke Island. After waylaying countless ships and stealing valuable cargo for more than two years, Blackbeard finally was beheaded by a British naval captain in 1718, in a slough off his beloved Ocracoke.

Settlement and sparse development continued through the early 1700s, and by 1722 almost all of the Outer Banks was secured in private ownership. Large tracts of land, often in parcels with 2,000 acres or more, were deeded to noblemen, investors and cattle ranchers. Some New England whalers also relocated to the barrier islands after British noblemen encouraged such industry. Whales were sliced open and their blubber, oil and bones sold and shipped overseas. The huge marine mammals were harpooned offshore from boats or merely harvested on the sand after dying and drifting into the shallow surf.

Although small settlements and scores of fish camps were scattered from Hatteras Village almost to the Virginia line, Ocracoke and the next island south, Portsmouth, continued to be the most bustling areas of the Outer Banks through the middle of the 18th century. British officials enlisted government-paid pilots to operate transfer stations at Ocracoke Inlet, between the two islands, and carry goods across the sounds to the mainland. A small town of sorts sprang up, as the people finally had found some steady occupation and were assured of regular wages.

In 1757 the barrier islands' first tavern opened amidst a sparse string of wooden warehouses and cottages on Portsmouth Island. About 11 years later, a minister made the first recorded religious visit to the Outer Banks when he baptized 27 children in the sea just south of the tavern. Today, a Methodist church and a few National Park Service-supervised cottages are all that remain on Portsmouth Island.

War and Statehood

As much of a hindrance as the string of barrier islands and their surrounding shoals and sounds had been to shipping, the Outer Banks proved equally invaluable as a strategic outpost during the Revolutionary War.

Only local pilots in small sailing sloops could successfully navigate the shifting sands and often unruly inlets that provided the sole passageway between the Atlantic Ocean and North Carolina mainland. So, big British warships could not anchor close enough to sabotage most Carolina ports. Colonial crafts, instead, ferried much-needed supplies through Ocracoke Inlet, up inland rivers and small waterways, to the new American strongholds in New England.

By the spring of 1776, however, British troops began threatening the pilots at Ocracoke, even boarding some of their small sloops and demanding to be taken inland, where they could better wage war. Colonial leaders then hired independent armed companies to defend the inlets. They abandoned these small forces by autumn of the following year. British boats, however, continued to beleaguer the Outer Banks. Ships landed along Currituck's islands, so sailors could steal cattle and sheep. The redcoats anchored off Nags Head, going inland for fresh water and whatever supplies they could pilfer. They raided fishing villages, plundered small sailboats and came ashore beneath the cloak of darkness. Ocracoke Inlet, especially, suffered under their persistent attacks.

In November 1779, North Carolina legislators formed an Ocracoke Militia Company, hiring 25 local men as soldiers to defend their island's independence. This newly armed force was issued regular pay and rations. Its members successfully saved the inlet and American supplies until fighting finally stopped in 1783, six years after the United States declared its independence.

About 1,000 permanent residents made their homes on the Outer Banks by the time North Carolina became a sovereign state under the 1789 Constitution. Most of these people sailed down from the Tidewater area of Virginia or across from the Carolina mainland. These hearty folk lived in two-story wooden structures with an outdoor kitchen and privy. They dug gardens in the maritime forests, built crude fish camps on the ocean and erected rough-hewn hunting blinds along the waterfowl-rich marshlands. After frequent storms crashed along their coasts, the residents continued to find profit in the shipwrecks strewn along nearby shoals and shores.

Lighthouses Along the Graveyard of the Atlantic

More than a dozen ships a day were carrying cargo and crew along Outer Banks waterways by the dawn of the 19th century. Schooners and sloops, sailboats and new steamers all journeyed around the sounds and across the oceans, often dangerously close to the coast in search of the ever-shifting and shoaling inlets.

More than a dozen ships a day were carrying cargo and crew along Outer Banks waterways by the dawn of the 19th century. Schooners and sloops, sailboats and new steamers all journeyed around the sounds and across the oceans, often dangerously close to the coast in search of the ever-shifting and shoaling inlets.

At that time, waterways were the country's primary highways, and North Carolina's barrier islands were the Grand Central Station of most eastern routes. Hurricanes and nor'easters, which still threaten Outer Banks locals, took many boats by surprise, ending their voyages and hundreds of lives. Statesman Alexander Hamilton dubbed the ocean off the barrier islands "The Graveyard of the Atlantic" because its shoals became the burying grounds for so many ships. Current-day estimates from scientists at the Coastal Studies Institute located on Roanoke Island are that close to 8,000 vessels have been lost along North Carolina's craggy coast and in other waterways. In an attempt to help seamen navigate the treacherous shoals, the federal government authorized the Banks' first lighthouses in 1794: one at Cape Hatteras in the fishing village of Buxton and the other in the Ocracoke harbor, on a half-mile-Iong, 60-mile-wide pile of oyster shells dubbed Shell Castle Island. Shell Castle Lighthouse first illuminated the Atlantic in 1798. The Cape Hatteras beacon took a little longer to erect. It was finally finished in 1802. Two subsequent structures have sat on the same Buxton spot, but the Shell Castle beacon has long since succumbed to the sea.

Ship captains complained that the early lighthouses were unreliable and too dim. Vessels continued to smash into the shoals. So in 1823 the federal government financed a 65-foot-high lighthouse on Ocracoke Island. The squat structure was whitewashed, with a glass tower set slightly askew on its top. It is the oldest lighthouse still standing in North Carolina.

Ship captains complained that the early lighthouses were unreliable and too dim. Vessels continued to smash into the shoals. So in 1823 the federal government financed a 65-foot-high lighthouse on Ocracoke Island. The squat structure was whitewashed, with a glass tower set slightly askew on its top. It is the oldest lighthouse still standing in North Carolina.

Officials raised the Cape Hatteras tower to 150 feet in 1854. Five years later, they built two new Outer Banks beacons, at Cape Lookout and on Bodie Island (which is open to climb). Both of those lighthouses were improved and rebuilt in later years.

On December 16, 1870, the third lighthouse at Cape Hatteras was illuminated. Standing 210 feet tall and using a multifaceted lens to refract its (then) whale-oil beam across miles of sea, this spiral-striped structure is the tallest brick lighthouse in the United States. In 1999, the lighthouse was moved 2,900 feet inland from its original location to protect it from tides and hurricanes that were threatening to erode its foundation and send this tall tower tumbling into the sea. At the time of the move, the lighthouse was only 15 feet from the ocean’s edge. Cape Hatteras Lighthouse is open to climb.

On December 16, 1870, the third lighthouse at Cape Hatteras was illuminated. Standing 210 feet tall and using a multifaceted lens to refract its (then) whale-oil beam across miles of sea, this spiral-striped structure is the tallest brick lighthouse in the United States. In 1999, the lighthouse was moved 2,900 feet inland from its original location to protect it from tides and hurricanes that were threatening to erode its foundation and send this tall tower tumbling into the sea. At the time of the move, the lighthouse was only 15 feet from the ocean’s edge. Cape Hatteras Lighthouse is open to climb.

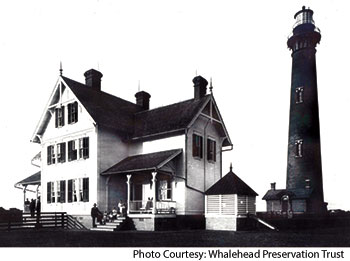

Currituck Beach's red-brick beacon was the last major lighthouse to be built on the barrier island beaches. A 150-foot tower that also is open for climbing and tours, this lighthouse was completed in 1875. It watches over the Whalehead mansion, near the western shores of Corolla. It is the only unpainted lighthouse on the Outer Banks and the only one held in private ownership. All other Banks beacons are owned by the National Park Service and operated by the U.S. Coast Guard.

Summer Settlements

In the early 1800s mainland farmers and wealthy families along Carolina's coast suffered each summer from the malady of malaria. They thought this feverous condition was caused by poisonous vapors escaping from the swamps on hot, humid afternoons. Physicians recommended escaping to the seaside for brisk breezes and salt air.

Nags Head was established as a resort destination primarily by a Perquimans County planter who bought 200 acres of ocean-to-sound land for 50¢ an acre in the early 1830s. Eight years later the Outer Banks' first hotel sprang from the sand near the sound, near what is now Jockey's Ridge State Park. Guests arrived at Nags Head Hotel from across the sounds on steamships, disembarked at a long, low boardwalk behind the 200-room hotel and spent weeks enjoying the beaches and the hotel's formal dining room, ballroom, tavern, bowling alleys and casino.

In 1851 workers enlarged the hotel and added a mile-long track of rails so mule-pulled carts could ease vacationers' journeys to the ocean. The hotel burned down and was rebuilt; later, it was buried by sand. Jockey's Ridge dune, the East Coast's tallest, swallowed the two-story structure bit by bit. Hotel clerks offered discounts during the final years for fellows who didn't mind digging their way into their rooms.

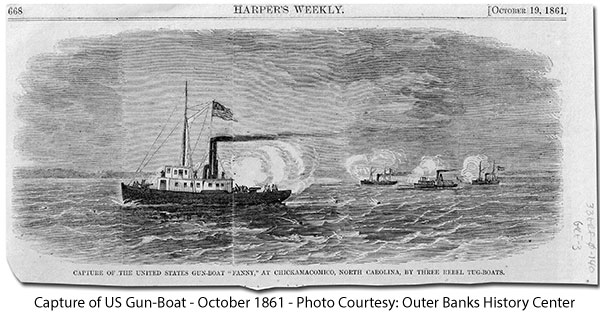

Civil War Skirmishes

Outer Banks inlets again proved important military targets after the War Between the States erupted in 1861. Union and Confederate troops stationed armed ships at Hatteras and Ocracoke inlets and set up early encampments. North Carolina crews, who joined their Southern neighbors and seceded from the United States, captured boats filled with fruit, mahogany, salt, molasses and coffee along the enigmatic inlets. Forts, too, were built along the barrier islands, although erosion and storms have long since erased all traces of such structures. Fort Oregon was constructed on the south side of Oregon Inlet; Fort Ocracoke on Beacon Island, inside Ocracoke Inlet. Fort Hatteras and Fort Clark were across from each other at Hatteras Inlet, by then the primary passageway between the ocean and sounds. Approximately 580 men defended those two forts. Seven cannons were mounted inside, aimed across the inlet from one fort to the other in a cross-fire position so that the entire waterway could be covered from within the high walls.

By the fall of 1861, however, federal forces had overtaken Hatteras Inlet and controlled most of the Outer Banks and lower sounds. Confederate troops still ruled Roanoke Island and the upper sounds. They built three small fortresses on the north end of their stronghold to reinforce their position and to block all access through Croatan Sound.

Union troops also were amassing. In January 1862 Gen. Ambrose Burnside led an 80-boat flotilla from Newport News to North Carolina's Outer Banks. Water was so scarce on this trip that some soldiers resorted to drinking vinegar out of sheer thirst. Others died of typhoid before the battle even began. But on February 7 more than 11,500 members of the federal army amassed for a Roanoke Island attack (an overlook at Northwest Point on the northern end of the island commemorates this site today). At least 7,500 men raided the shores at Ashby's Harbor that night, near Roanoke Island's present-day Skyco. About 1,050 Confederate soldiers fought to maintain their foothold.

After hours of battle around what is now the Nags Head-Manteo Causeway, the rebel troops finally were forced to surrender. Union troops captured an estimated 75 of these Southerners. Federal forces held Roanoke Island, and most of the Outer Banks, for the rest of the Civil War.

A Settlement for Freed Slaves

After Roanoke Island fell to Union troops, Union leaders had to decide what to do with the slaves from the former Confederate camp. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler at Fortress Monroe set a precedent by declaring slaves as contraband, successfully using the notion against the rebels. Word spread of this action, and black women and children began flocking to Union camps where they were allowed to settle peacefully. Once word reached the underground network of servants, abolitionists and free blacks, the number of freedom-seeking folk migrating to Dare and Currituck counties increased. At the outbreak of the Civil War, only a few hundred slaves lived along the Outer Banks. But two months after falling to Union troops, Roanoke Island was filled with more than 1,000 runaway and recently freed slaves. Inhabitants of the colony worked porters for Union officers and soldiers and as cooks, teamsters and woodcutters. The federal government offered these African-American men $8 per month plus rations and clothing to build a fort, Fort Burnside, on the north end of Roanoke Island. Women and children, who made up three-fourths of the population of blacks on the island at that time, collected only $4 a month, including clothing and ration benefits.

By June 1863, officials had established an official Freedmen's Colony on Roanoke Island. The government granted all unclaimed lands to the former slaves and outfitted them with a steam mill, sawmill, grist mill, circular saws and other necessary tools. About 3,000 African Americans lived here in a village with more than 600 houses, a school, store, small church and hospital.

Union forces began accepting African-American troops soon after they established the settlement. By the end of July, more than 100 members of the Freedmen's Colony formed the nation's first African-American army regiment. The new colony would have survived were it not for the government's decision to return all lands to the original landowners after the war was over. The Freedmen's Colony was abandoned in 1866. Federal officials quickly transported many of the former slaves off the Outer Banks. Others remained on Roanoke Island to work the waters and the land.

Brave Men and Britches Buoys

After the war, normal life resumed on the barrier islands. Commerce commenced again along the ocean, increasing quickly with steamers now outnumbering sailboats and onetime warships joining private shipping companies. Storms, too, continued to wrack the shores and seamen, sometimes even sinking iron battleships into oblivion.

After the war, normal life resumed on the barrier islands. Commerce commenced again along the ocean, increasing quickly with steamers now outnumbering sailboats and onetime warships joining private shipping companies. Storms, too, continued to wrack the shores and seamen, sometimes even sinking iron battleships into oblivion.

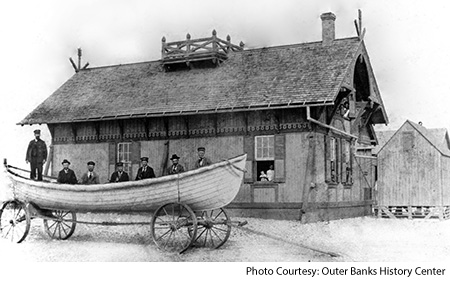

Seven U.S. Lifesaving Stations were established on the Outer Banks in 1874 in an attempt to help save sailors' lives, if not salvage some of the ships. The stations included: Jones's Hill near the Currituck Beach Lighthouse; Caffrey's Inlet north of Duck; Kitty Hawk Beach south of the present pier; Nag's (sic) Head within current town boundaries; Bodie's (sic) Island south of Oregon Inlet; Chicamacomico, which is open to visitors in Rodanthe and conducts simulated rescue drills each summer; and Little Kinnakeet, on the west side of N.C. 12 in Avon.

During their first season of employment, lifesaving station keepers were paid $200 per year to supervise six surfmen from December through March. Lifesavers lived in the sparse wooden stations, often sleeping six to a room, and kept constant watch over the Atlantic from inside elevated towers that poked out of the stations' roofs. The men walked the beach 24 hours a day. Two from each station would leave at the same time, one heading north, the other south. After 3 to 6 miles, they'd meet a surfman from the neighboring station, also walking either north or south, and exchange tokens to prove they had completed their patrol.

Stations were operated mostly by longtime Outer Bankers. Good swimmers and sea captains who knew the wild waters, these men risked their lives (and many perished) trying to pull others from the ocean. During the winter of 1877-78, more than 188 shipwreck victims and surfmen died within a 30-mile stretch of beach on the northern Outer Banks. That summer, Congress authorized 11 additional lifesaving stations, including ones for Wash Woods and Penny's Hill in Carova, Kill Devil Hills, Hatteras and Pea Island (which had an all-African-American crew). The Lifesaving Service also added a seventh surfman to each station. Crews were then employed from September through April. Rescue techniques advanced with new equipment and the surfmen's experience in ocean survival.

Stations were operated mostly by longtime Outer Bankers. Good swimmers and sea captains who knew the wild waters, these men risked their lives (and many perished) trying to pull others from the ocean. During the winter of 1877-78, more than 188 shipwreck victims and surfmen died within a 30-mile stretch of beach on the northern Outer Banks. That summer, Congress authorized 11 additional lifesaving stations, including ones for Wash Woods and Penny's Hill in Carova, Kill Devil Hills, Hatteras and Pea Island (which had an all-African-American crew). The Lifesaving Service also added a seventh surfman to each station. Crews were then employed from September through April. Rescue techniques advanced with new equipment and the surfmen's experience in ocean survival.

Before motorized rescue craft were available, lifesaving teams had to row deep-hulled wooden boats, often through overhead waves. If they made it through the seething seas to shipwrecks, they sometimes couldn't carry all of the sailors back to shore in one trip. As a result, they devised a pulley system to haul men off the sinking vessels. Dubbed a "Britches Buoy," the device consisted of a pair of short pants sewn around a life preserver ring and hung on a thick rope by wide suspenders; the rope was wound around a handle crank mounted to a wooden cart on shore. Shipwreck victims struggled into the britches, usually with the assistance of surfmen in the rescue boat, and gave an "all-clear" tug on the rope. With the buoy sewn into the seams around their waists, these sailors didn't sink. Even in the highest seas, they could keep their heads above water while lifesaving crews back on shore reeled them safely onto the sand.

Surfmen at Outer Banks lifesaving stations saved thousands of lives during hurricanes and hellacious northeast blows. In 1915 the Lifesaving Service became part of the U.S. Coast Guard. Coast Guardsmen continue to aid barrier island boaters with a variety of state-of-the-art rescue craft stationed at modern Oregon Inlet and Hatteras Island stations.

Historic Happenings, Modern Influences

In 1902, however, the barrier islands recorded another first when Thomas Edison's former chief chemist began experimenting with wireless telegraphy. Radio pioneer Reginald Fessenden transmitted the first musical notes to be received by signal from near Buxton on Hatteras Island to Roanoke Island. He wrote to his patent attorney that the resulting sounds were "very loud and plain, i.e., as loud as an ordinary telephone."

In 1900 Ohio bicycle shop owners Wilbur and Orville Wright arrived by boat at Kitty Hawk, looking for reliable winds. Three years later, on December 17,1903, the Wright brothers soared over Kill Devil Hills sand dunes in the world's first powered airplane. Only a handful of local Bankers looked on in amazement as the flyer stayed aloft for 59 seconds, flying 852 feet. The site is now marked with a stone monument in a National Park, Wright Brothers National Memorial, set along the original runway. A replica of the historic airplane, hangar and brothers’ shack are on display.

In the 1930s, bridges linking the Outer Banks to the mainland brought thousands more tourists and profound changes to the islands. Visitors now could drive to popular summer resorts at Nags Head rather than rely on steamships. Hotels, rental cottages and restaurants sprang up to accommodate the influx.

Post-Depression era politics promulgated the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCG), which set up six camps along the barrier islands. Throughout the '30s, these government workers performed millions of dollars’ worth of dune construction and shoreline stabilization. The dunes you see along the east side of N.C. 12 did not grow that tall naturally. CCC workers planted much of the grass and scrubby shrubbery to help stave off erosion along the ocean.

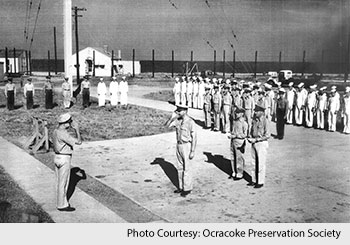

Although it was mostly waged continents away, World War II spread all the way across the ocean to the Outer Banks' doorstep. German U-boats lurked in near-shore shipping lanes, exacting heavy losses to Allied vessels. At least 60 boats fell victim to the submarines, though the Germans experienced losses of their own: The first U-boat sunk by Americans lies in an Atlantic grave off the coast of Bodie Island. Longtime barrier island residents recount having to pull their shades and extinguish all lights each night during the war so ships and submarines could not easily discern the shoreline.

Although it was mostly waged continents away, World War II spread all the way across the ocean to the Outer Banks' doorstep. German U-boats lurked in near-shore shipping lanes, exacting heavy losses to Allied vessels. At least 60 boats fell victim to the submarines, though the Germans experienced losses of their own: The first U-boat sunk by Americans lies in an Atlantic grave off the coast of Bodie Island. Longtime barrier island residents recount having to pull their shades and extinguish all lights each night during the war so ships and submarines could not easily discern the shoreline.

Talk of the country's first national seashore began in the 1930s. By 1953, when the Cape Hatteras National Seashore finally was established under the auspices of the National Park Service, it stretched from Nags Head through Ocracoke Island.

Today, the Outer Banks are some of the most popular yet pristine beach resorts on the Atlantic coast. A bit more than 35,000 people make the barrier islands their permanent home. But close to a half-million visit our sandy shores during the summer high season.