SEEDS TO SOCIETY:

Conversations with Organic Farmers in Eastern North Carolina

Somerset Farm: Old-Style for the Future

Garlic, beets, turnips, sweet bell peppers, tomatoes, eggplant, zucchini, squash, watermelons, cucumbers, daikon, radishes, kale, and sweet potatoes. That doesn’t even cover all the beautiful fruits and vegetables that occupy the Somerset Farm table at the Manteo Farmer’s Market on a Saturday morning.

Garlic, beets, turnips, sweet bell peppers, tomatoes, eggplant, zucchini, squash, watermelons, cucumbers, daikon, radishes, kale, and sweet potatoes. That doesn’t even cover all the beautiful fruits and vegetables that occupy the Somerset Farm table at the Manteo Farmer’s Market on a Saturday morning.

Hazel Inglis grew up on roughly 80 acres of land that has been owned by her family since her great grandfather’s time. Her father, Frederick Inglis, converted 20 certified organic acres into what is now Somerset Farms. For her father, farming is a way of life, something he is good at and that he takes pride in. Hazel has grown up around this way of life, but she explains that it is not just waking up to the rooster and picking tomatoes.

The meaning of organic can get lost in all the health crazes and theories about what should and shouldn’t be eaten. “Organic farming is pretty personal to me, you know, because of my father,” says Hazel. “And, to me it’s just good quality food…the process of the food takes care of the land.” Organic farming avoids putting chemicals into the soil that aren’t already there; it’s as simple as that.

As Hazel explains, there was not much of a demand for organic food until about the last decade. People are noticing a difference now, whether because of health concerns or taste preferences. Hazel says she hears comments like, “I never liked eggplant until I had your eggplant; it had such a rich taste and was so good,” or, “I didn’t know you could eat the tops of that!” And Hazel will respond, “Yeah, it’s really good and really good for you.” She explains that the shift in consumer demand is in part because of a changing population in the Eastern North Carolina region. People from other parts of the country are moving here—and with more money.

Access to organic produce can be a problem for lower income people, people who don’t live near fresh food or for people who aren’t educated on what good food means. Somerset Farm is doing what it can to close that gap. They sell their produce at the Edenton Farmer’s Market at the same price as conventional farmers. That means that people pay the same price they would at a grocery store while getting better quality food.

Access to organic produce can be a problem for lower income people, people who don’t live near fresh food or for people who aren’t educated on what good food means. Somerset Farm is doing what it can to close that gap. They sell their produce at the Edenton Farmer’s Market at the same price as conventional farmers. That means that people pay the same price they would at a grocery store while getting better quality food.

Frederick Inglis would avoid dealing with transactions and dedicate all his time to being on the land if he could, but Hazel says it is good for him to interact with the people who enjoy the food he grows. “There’ve been years past where he hasn’t gone to the farmer’s market. And, I think it’s good when he does have to go to the farmer’s market. People are like, ‘Oh you’re the farmer,’ and they thank him. I think it’s really great for him to interact with the public and get positive feedback.” Back on the farm, you’ll see Mr. Inglis still using a horse when he can to plough his land and a variety of livestock, as if it were a snapshot of the early 1900s. This reduces compaction of the soil by tractors that makes it harder for crops to thrive.

Farm work can be frustrating, stressful and far from glamorous. Just ask Hazel about the time she delivered about $4,000 worth of produce when the truck’s breaks stopped working and she literally rolled to a stop at her destination. But hard work pays off. “There’s this one little seed and it becomes a crop you can eat,” says Hazel. “I like going to bed with my muscles aching. I like that. I like when you plant a crop...you watch them grow. You weed. You chop. You hoe. You pick it, and then you sell it. It’s really amazing to see the whole process.” Hazel says that her father gets a similar joy out of getting his hands dirty surrounded by the beautiful piece of land that his grandfather once worked.

Hazel will not hesitate to tell you that she has a hard time imagining herself taking over her father’s farm and making it a life-long dedication, as her father might like. She explains that it is even harder for young people to choose farming as career when they haven’t grown up with it.

Land is expensive, regulations are harsh for small farms, and there is always the risk that crops will fail. Does that mean that we let our dependence on large conventional farm’s increase and our connection to food be severed further? The Inglis’ would almost certainly disagree.

It is understandable why people may mistake the size of conventional farms as being more productive. It seems reasonable that spraying pesticides would be better than a crop failing from a harmful organism. But the public needs to start thinking about the future of food, and more specifically of the land that produces it. The Inglis’, and other organic farmers, avoid using chemicals in their farming for the health of people as well as the longevity of their operation.

Agricultural land can become less productive as chemicals in fertilizers and pesticides and modern machinery affect the complex system and organisms that live below the surface. The well-being of this micro-ecosystem is vital to farming and consequentially to feeding society. Though Somerset Farm is utilizing techniques dating back to an earlier era, the Inglis family is certainly considering the future of food production.

Looking Back Farm: It’s all About the Domino Effect

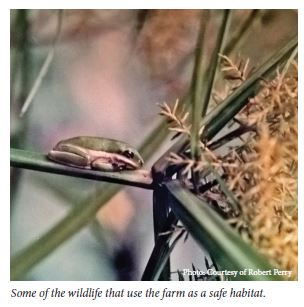

As a young organic farmer on his family’s land, Robert Perry had an appreciation for the land around him and the diverse array of species that came with it. His love for the environment is quick to come across in his storytelling, like when speaks about his father prodding him to kill several cottonmouth snakes with a shotgun after they were exposed from a large tree falling down on the farm. He couldn’t bring himself to kill the aggressive snakes and instead spent an afternoon relocating them one by one to a nearby swamp. “I have a huge soft place in my heart for all snakes, poisonous or not. I just think they are all part of the ecology and they all need to be there and it’s their home as much as ours, perhaps even more so.”

As a young organic farmer on his family’s land, Robert Perry had an appreciation for the land around him and the diverse array of species that came with it. His love for the environment is quick to come across in his storytelling, like when speaks about his father prodding him to kill several cottonmouth snakes with a shotgun after they were exposed from a large tree falling down on the farm. He couldn’t bring himself to kill the aggressive snakes and instead spent an afternoon relocating them one by one to a nearby swamp. “I have a huge soft place in my heart for all snakes, poisonous or not. I just think they are all part of the ecology and they all need to be there and it’s their home as much as ours, perhaps even more so.”

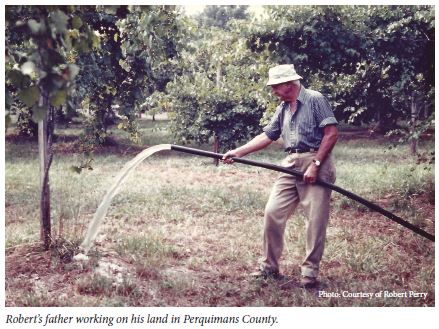

In the 1950’s, Perry’s father went about reacquiring land in Perquimans County that he discovered belonged to his ancestors. He found his family’s name associated with a large area of land roughly 200 years ago while looking through historical records. This acquisition meant a great deal to Perry’s father—it meant he was connecting his family’s past, present, and future. “He wanted to buy land because he was a child of The Depression and felt that land was the only thing that would get you through another major economic downturn. To buttress his financial self, as well as, the future of his children he thought he’d by farm and swamp land. Ultimately he pieced together 500 acres in Perquimans Country.”

In the 1950’s, Perry’s father went about reacquiring land in Perquimans County that he discovered belonged to his ancestors. He found his family’s name associated with a large area of land roughly 200 years ago while looking through historical records. This acquisition meant a great deal to Perry’s father—it meant he was connecting his family’s past, present, and future. “He wanted to buy land because he was a child of The Depression and felt that land was the only thing that would get you through another major economic downturn. To buttress his financial self, as well as, the future of his children he thought he’d by farm and swamp land. Ultimately he pieced together 500 acres in Perquimans Country.”

After graduating college, Robert considered pursuing the career of a farmer and did so for a couple of years. He appreciated the fact that he could grow anything he wanted, except chickpeas. Apparently they are tricky. He wanted to sell what food he grew to the public, but back then organic food wasn’t being sought out like it is today. “There was very little demand for organic food. People were just buying it because it happened to be what it was, a tomato, or a cucumber, or a cantaloupe, but not because it was being sold organically. They didn’t really care whether it was organic or not.” The difficulty of being an organic farmer, the feeling of isolation, and the desire to go to grad school brought Robert to New York, hoping one day to return to the land and the purpose.

It took 30 years but Robert eventually made his way back to North Carolina and his literal and figurative roots. It wasn’t possible for him to return to being a full-time farmer as he would have hoped, but he has since become a master gardener. He shares his vast knowledge of growing food to many people and also started a community garden aimed at helping immigrant families get inexpensive, healthy food in Manteo. Robert contributes what he can to the organic movement by gardening, but he speaks about how maintaining a relationship with the farmers on his land is reaching an even larger goal. “Our whole reason for doing it organically is to try to maintain a biodiverse ecosystem out there in that little area of farmland. And hopefully get enough other farmers interested so that we can act as nexus for spreading out beyond that particular point.”

Robert and his brother and sister inherited the large plot of land when their father passed in 2001. The Perry children have since spread across the United States, but they have maintained a vision for the land that their father would have approved of. “We feel that we provide an oasis for the animals inhabiting the area to breathe and to grow without the impact of pesticides.” They have done so by renting the land to the same farmers that their father did when he grew older, Kenny and Ben Haynes.

Robert has kept a close relationship with the duo, Kenny and his son, visiting the farm when he can and conversating about all things organic. “They will talk your ear off about how evil Monsanto is. The consolidation of entire food and agri-businesses continues to cut out small farmers and cut out organic farmers…they’re looking at this from a very large, holistic perspective to try to keep large ecosystems healthy.”

Robert has kept a close relationship with the duo, Kenny and his son, visiting the farm when he can and conversating about all things organic. “They will talk your ear off about how evil Monsanto is. The consolidation of entire food and agri-businesses continues to cut out small farmers and cut out organic farmers…they’re looking at this from a very large, holistic perspective to try to keep large ecosystems healthy.”

Kenny and Ben have been farming the Perry’s land since they responded to a paper advertisement for an organic farmer in the 1990s. They have worked immensely to create a very healthy soil that provides many benefits that the traditional sandy Eastern North Carolina soil does not. Robert speaks proudly of their efforts to increase the quality of the soil using something called mushroom compost residue: “These guys have figured out a way to go up there and truck that stuff down to the farm and put it on the land. The land is now so full of organic material that it actually holds water much better than local other farmers nearby. When there’s a drought and it rains the, organic farmers land will hold the water far better than the other farmers who experience a lot of drought. Pretty amazing to see.” These efforts have caught the attention of other farmers in the area and the organic bug seems to be spreading. “There is a growing interest in neighboring farmers about what these guys have been doing. It may take a pretty substantial foothold right in that area in the next couple years.” Once these farmers gain knowledge about how and why to go organic, they can act as role models for an even wider range of people.

What if this trend continued, where a community was more invested in where their food came from and who grew it? Maybe it would make the life of a farmer just a little bit easier if they weren’t so isolated from the public. This would mean organic farming would have to become the norm and somehow push the giant conventional farms out of the picture. Hopefully, this would look like smaller farms, more of them, and people embracing them as a key to part to making communities thrive. Robert seems to be ahead of the game and for all the right reasons.

Weeping Radish Brewery Farm: Say Hello to the Farmer

There is no denying that America’s health is far from perfect and that access to affordable, nutritious food is part of the problem. Uli Bennewitz will tell you that this epidemic is not McDonalds fault. Their job was to make a dollar burger, and they succeeded at that, impressively. The problem with food quality and food access is where and when the nation spends money. “You either pay now or pay later, that’s what this is all about. The whole local food movement is all about spending more money upfront on your food, and that’s the only way in the long-term that we are going to reduce healthcare costs.” Uli makes this statement with the implication that eating organic, local food is healthier than the sugary, processed food that seems to prevail from sea to shining sea. If improving the health of the nation is that simple, why isn’t everyone on board yet? It’s because providing better food, and then making people eat it, will take a paradigm shift of immense proportions in eating and spending habits.

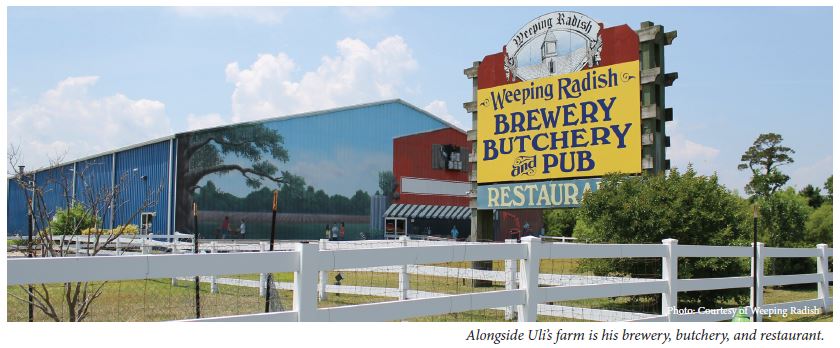

Uli Bennewitz is a man of many trades, one of which is organic farming. He owns Weeping Radish Farm Brewery in Grandy, North Carolina, where he provides tours, microbrews and farm–to–table meals. He grew up in Germany and went to university in England for farming education. He came to North Carolina with his wife right after he finished school, because without land to be inherited in England he wasn’t going to be a successful farmer. His first job in the States was unsurprisingly in land development. He helped make 7,000 acres on fields just west of the Outer Banks agriculturally productive, and he is proud of that work.

Uli hates labels and believes they can stunt the very thing they are set out to encourage—even the “organic” label. In 2000, Uli bought land in Currituck and started his own farming operation. Since the idea of farm to fork was relatively new, labeling himself as organic was a risky business move. Uli is a bit of an anomaly, so his experience breaking into organics was a bit easier than usual. “In 2000, if you talked about things like that, sustainable, organic, all these issues, you were considered a left wing extremist…in my case it was hilarious because I was managing at that time 15,000 acres of conventional farming, so nobody could call me a left wing nut. I was on both sides, so it was much easier for me to get into that movement because I didn’t have the label that a lot of these other organic-oriented people had.”

Uli hates labels and believes they can stunt the very thing they are set out to encourage—even the “organic” label. In 2000, Uli bought land in Currituck and started his own farming operation. Since the idea of farm to fork was relatively new, labeling himself as organic was a risky business move. Uli is a bit of an anomaly, so his experience breaking into organics was a bit easier than usual. “In 2000, if you talked about things like that, sustainable, organic, all these issues, you were considered a left wing extremist…in my case it was hilarious because I was managing at that time 15,000 acres of conventional farming, so nobody could call me a left wing nut. I was on both sides, so it was much easier for me to get into that movement because I didn’t have the label that a lot of these other organic-oriented people had.”

Uli will tell you that the farm–to–fork movement had great intentions, but somewhere along the way it got off track. The Carolina Farm Steward Association (CFSA) used to be the certifying body for NC farms and has conventions with farmers to aid them in any way possible. “They used to meet in the mountains of North Carolina in some weird place they could seat a 100 people and had some kitchen facilities. Now they meet in the Raleigh convention facility.” This is a metaphor for what’s happening to the agricultural industry in the US. Now the USDA does any and all organic certification for farmers, and Uli says that has really hurt the small organic farmers. “The whole idea of a local group doing their own certification makes perfect sense in my book, because the tougher their standards, the better reputation of that local group. Once you’re in a federal system, who cares, just fill out your paper, get your stamp and you’re in the same league as anybody else…it turns it into a commodity on its own and the whole thing about organic is it didn’t used to be a commodity.”

Not only does the new certification process put large-scale farms at the same table as small operations, but also the term organic has been overextended to the point of being almost meaningless. Uli soon caught on that getting certified was more a burden than anything, seeing that small organic farms like his had more restrictions and regulations than the giant conventional ones. When starting his Currituck farm, Uli looked for stores that would be a good market for his produce. One store owner, Uli recalls, said “‘We love your vegetables, but we can’t sell them because they aren’t certified.’” Ironically, the organic food sold in that particular store had traveled thousands of miles. “He opened my eyes for me…he showed me a pound of organic Brussel sprouts in his freezer, and it was USDA certified organic, California certified organic, and underneath all of them it said product made in China. I walked out of that store and quit organic farming because I will not compete with China.” Not only was the USDA certifying the entire U.S. at this point, but they were also the certifying body for many of the farms in China that were exporting to the U.S.

To be clear, Uli didn’t stop organic farming, he just forewent the label. The CFSA has changed drastically in terms of who the organization is made up of and what those people do. “80% will be consultants, government folks, university folks, all the hanger-ons that hang on to those 20% that physically do all the work.” What was originally a group made up of primarily farmers is now a group of suits that will pat the local farmer on the back and then turn around to support Chinese produce infiltrating the U.S. organic market. Organic farmers are dealing with foreign competition, a problem that these “hanger-ons” are hiding from the general public.

The other groups that are benefiting at the expense of the organic farmer are the large conventional farms. These big guys have their complaints, but at the end of the day they are able to grow and crowd out the market. Uli thinks this is a hard process to reverse. “It’s very scary because one of the things that has happened in Illinois or anywhere in farming is consolidation. In Illinois, they are closing local schools because nobody lives there anymore, because farms are getting bigger and bigger and require fewer and fewer people, and all the young kids leave. I call it rural brain drain, which is a sad statement you have to make.” We can’t let this scary thought stunt the growth of the organic movement. Uli says that his generation owes it to the future to run like hell from all the mistakes that have been made. Or maybe spend like hell instead.

The other groups that are benefiting at the expense of the organic farmer are the large conventional farms. These big guys have their complaints, but at the end of the day they are able to grow and crowd out the market. Uli thinks this is a hard process to reverse. “It’s very scary because one of the things that has happened in Illinois or anywhere in farming is consolidation. In Illinois, they are closing local schools because nobody lives there anymore, because farms are getting bigger and bigger and require fewer and fewer people, and all the young kids leave. I call it rural brain drain, which is a sad statement you have to make.” We can’t let this scary thought stunt the growth of the organic movement. Uli says that his generation owes it to the future to run like hell from all the mistakes that have been made. Or maybe spend like hell instead.

Imagine a new residential development that surrounds an area of land for children to play in, community activities to be held, and then imagine an organic farm also occupying that area. Sound crazy? It already exists, and it is serving its purpose beautifully. Uli believes in the power of connecting people to their food to solve many of the public’s problems, and it can be hard to sell that idea to decision makers. But Uli has a knack for making politicians and academics scratch their heads. He’ll tell you a story about a senator who visited Weeping Radish who will probably never think about her job and responsibilities in the same way again. “She was supposed to spend 5 minutes, take a picture and run out the door. She spent an hour there.”

After that hour, Uli said that the senator was impressed but thought this type of operation couldn’t be implemented elsewhere because it was too expensive. Clearly recalling the conversation, he said, “Ma’am, on your way back to Raleigh, you will drive through a town called Plymouth, North Carolina. Plymouth has about 6,000 people living there. Plymouth has seven fast food joints.” And I asked, “You know what else they have in Plymouth?” She said, “No what?” I said, “A dialysis center.” That is the issue…but don’t blame McDonalds.”

The real problem with the farming system in the U.S. is the missing connection between farmer and foodie. The public needs to be better exposed to what good quality food is, how it is grown, where it comes from and the health consequences of eating processed foods. Uli says we need to run like hell from the mistakes his generation made and that the direction is pretty clear: focus on the little guys, the small organic farmers. Advocacy is just a fraction of the shift, meaning the real change must come from doers, like himself. Though the government can help by putting less money toward the nation’s large conventional farms, the change needs to happen in each household. As Uli will argue, the grassroots movements come as a result of education. So, take the weekends to go to your farmers markets and farm tours, and find a way to bring the farmer face-to-face with younger generations.

Roanoke Island Community Garden: Nourishing the Soil, the Soul, and Society

After talking with some folks who are already avid organic farmers, it was time to hear from someone who is in the process of learning how to grow organically. Small-time gardener Linda Morgan has been growing little plots throughout her life, but she is now trying to go sans chemicals. She may not be tending to a full-scale farm, but her efforts have big implications.

After talking with some folks who are already avid organic farmers, it was time to hear from someone who is in the process of learning how to grow organically. Small-time gardener Linda Morgan has been growing little plots throughout her life, but she is now trying to go sans chemicals. She may not be tending to a full-scale farm, but her efforts have big implications.

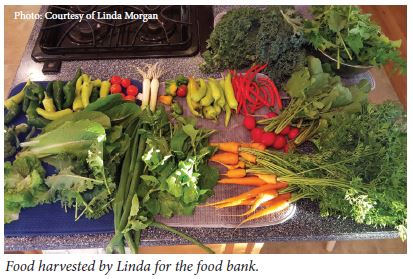

Linda spent many years caring for people as a nurse, and after retiring she continues that effort through food. She maintains an entire community garden plot just to provide fresh produce to the local food bank on Roanoke Island. She has two plots of her own as well, one at the garden and one at her home. “To me it means not using synthetic stuff and not using chemicals to the biggest extent that you can. That’s the first step I want to take. I want to try to limit my use of things that could be harmful to me or to whoever else might eat my food.” Linda does not use fully organic methods at the moment, but she looks forward to a future where she has the knowledge and resources to do so.

Linda struggles to control troublesome bugs in her garden, but she is learning more about the consequences of using pesticides and insecticides. “I’m thinking twice about that now, knowing that the bad stuff not only kills what you want killed but some other things that you don’t want killed. I’m reading up on it a lot, learning a lot, so hopefully next year I’ll be more toward organic.” Linda is excited about using her personal compost instead of nitrogen heavy fertilizers, as everyone should be doing in her opinion. Most store bought fertilizers take a large amount of energy to be produced, only to leave the soil devoid of natural nutrient cycles and hungry for more processed dirt.

Linda’s drive to go organic extends beyond just giving back to the earth—she wants to keep from taking opportunities from future generations. “The environment is what sparks it. I’ve got two little grandkids. I want them to be safe. I want the food they eat to be safe. I want the grass they walk on to be safe. I want them to appreciate nature.” Linda is able to think about her actions in a larger context and tries to share that mentality with her family. When she and her grandkids are playing outside she tells them, “You don’t need to kill bugs just because they’re bugs.”

Linda’s drive to go organic extends beyond just giving back to the earth—she wants to keep from taking opportunities from future generations. “The environment is what sparks it. I’ve got two little grandkids. I want them to be safe. I want the food they eat to be safe. I want the grass they walk on to be safe. I want them to appreciate nature.” Linda is able to think about her actions in a larger context and tries to share that mentality with her family. When she and her grandkids are playing outside she tells them, “You don’t need to kill bugs just because they’re bugs.”

As much of a difference as growing organically can make, Linda points out that getting there is not always easy. Trial and error has definitely been a part of the learning process for her. “I’ve had such a great time watching the little things grow up...or not. It’s interesting to think what might I have done wrong? Did I plant it at the wrong time? Was it too cold? Was it too wet? Is this something that shouldn’t be grown here? It’s just been really, really interesting.” Unfortunately, not a lot of people have the time to invest in managing a garden. The attention it requires is akin to babysitting a toddler—you never know what they’re going to do or when they’re going to get sick. This would be especially difficult for people who are struggling to get enough food on the table. Linda proposes, “There could be courses set up on organic farming—I’m sure there are some already—that could be a big help to people, like me, who don’t know a whole lot about it.” Perhaps it would be more effective to teach people how to and why it is important to grow healthy food, as opposed to putting it in their hands and saying bon appétit.

Spending 3 to 4 hours a day at the community garden is not unusual for Linda. “I love it. Its relaxation for me. Its exercise for me. I love being out there with the sun and the breeze blowing.” She takes a great deal of pride in the work she does and the product she shares with people in need. This passion for organic food is the key to shifting society to a more sustainable, healthy future. People will continue to choose cheap, conventional produce until they learn that organic food is a healthy and viable option. Linda, as many others do, believes that starting a conversation about food is the first step. What better place than the dinner table?

Hello Outer Banks folks! I’m a college student from UNC-Chapel Hill, and I’ve had the incredible opportunity to study on the Outer Banks this fall. Along with taking classes and conducting research, I got to talking with some Eastern North Carolina organic farmers. I’ve compiled what they said and what I’ve learned here, in the hopes of making people more invested in where their food comes from. Hope you enjoy and pass it along!

Hello Outer Banks folks! I’m a college student from UNC-Chapel Hill, and I’ve had the incredible opportunity to study on the Outer Banks this fall. Along with taking classes and conducting research, I got to talking with some Eastern North Carolina organic farmers. I’ve compiled what they said and what I’ve learned here, in the hopes of making people more invested in where their food comes from. Hope you enjoy and pass it along!